A Stunning Great Bible

W

e are excited to offer a spectacular copy of the 1541 Great Bible. A tall, complete example of the sixth edition (November 1541), described, certified, and gifted by Francis Fry to his daughter.

Francis Fry was one of the most important Bible collectors and bibliographers of the 19th century, known for his meticulous scholarship and publications on Tyndale’s New Testaments, the Great Bible, and the 59-line folio editions of the King James Version.

Fry wanted the best for his daughter. He likely had this copy rebound by the best binder he could find, the restoration work done by the best conservator he could find, and the few facsimile letters done by the best artist he could find.

That best binder was “Cross, binder to the Queen.” That best artist was likely John Harris Jr., who specialized in pen facsimile work.

The result is summarized by Fry’s own hand, in a note tipped into the volume: “I have examined it all through and certify that every leaf is the true edition.” He inscribed this copy to “Priscilla Anna Fry from her loving Father Francis Fry, Tower House, Cotham, Bristol 1881.”

This Bible has recently sold, but you can see our other Great Bible via the link below.

Importance of the Great Bible

The Great Bible of 1541 is a landmark in the history of the English Bible. Drawing heavily on the translation work of William Tyndale, it paved the way for later Protestant versions such as the Geneva Bible and the King James Version. Its publication marked a dramatic and unexpected shift: from the execution of translators to the royal authorization of English Scripture.

Under the Constitutions of Oxford, it was illegal to translate the Bible into English without church permission. Tyndale sought approval and was denied by Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of London. Undeterred, he left England in 1524 at the age of 30 and completed his groundbreaking English New Testament in 1526, printed in Germany and smuggled into England.

For this act of heresy, Tyndale was strangled and burned in 1536 by order of the very king who would authorize the first English Bible just three years later.

Henry VIII, a staunch Catholic who had written a treatise against Martin Luther and been named “Defender of the Faith” by the Pope, took personal pride in Tyndale’s capture. Yet Henry’s vendetta against reformers was soon eclipsed by his desire for a male heir, what contemporaries called “the King’s Great Matter.”

Henry sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and when his request was denied by the pope, opted to break from Rome. He became a catholic without a pope. Through the Act of Supremacy, Henry had himself declared head of church and state. With the encouragement from Thomas Cranmer, he authorized the translation of the Bible into English.

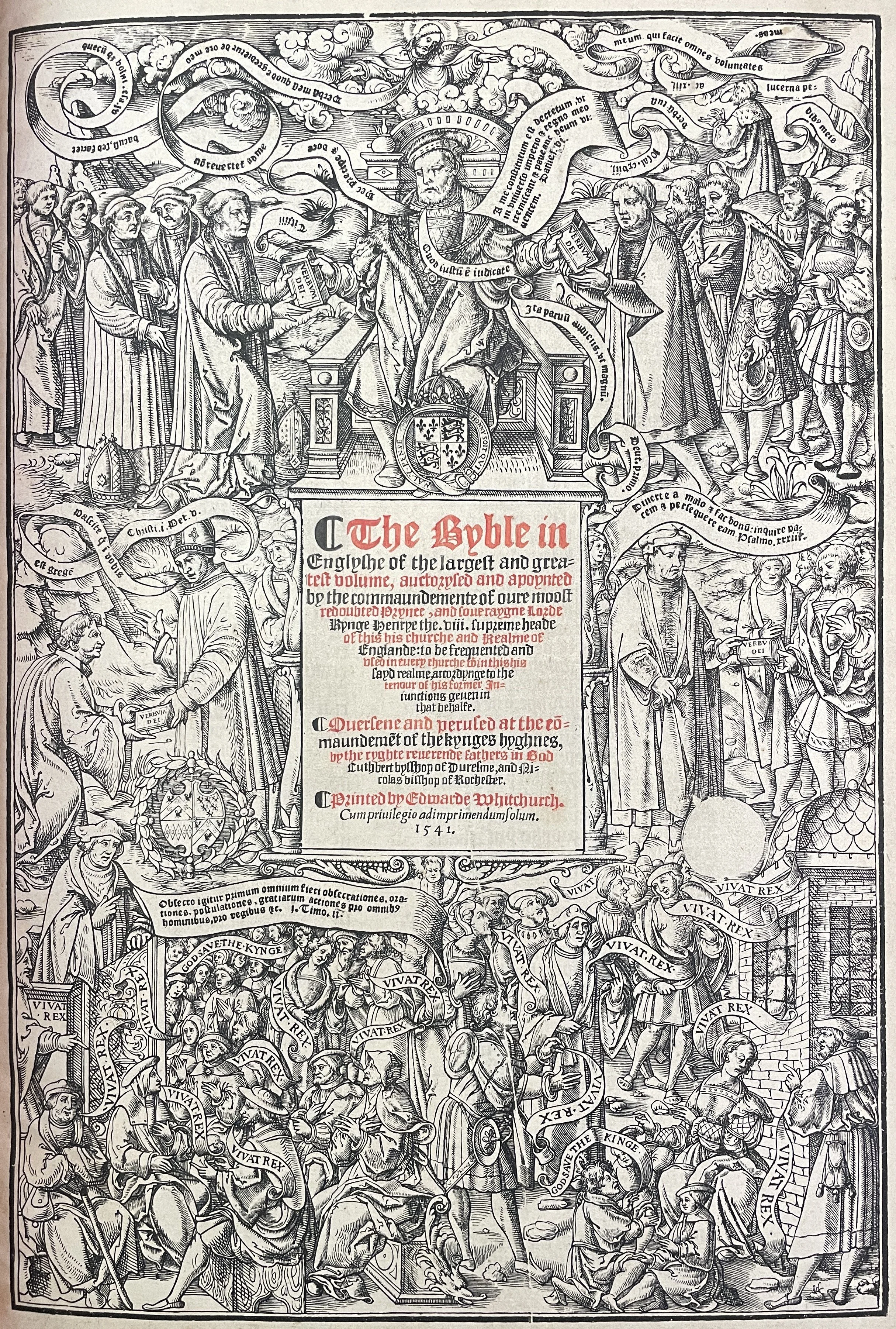

The title page of the Great Bible tells the story. At the top, Henry VIII dominates the scene, symbolizing the replacement of papal authority with royal supremacy. Above him, God is barely visible among the clouds. To Henry’s left and right stand Archbishop Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, who pass the Verbum Dei to the clergy and nobility.

Yet, the common people do not receive the Bible directly as it is chained to pulpits. Nevertheless, the crowd below proclaims "Long Live the King" in Latin, while those who remain silent appear imprisoned in the lower right corner.

Tyndale’s Influence Preserved

When tasked with producing the first official English Bible, Cranmer and Cromwell turned not to fresh translation work, but to a careful revision of the 1537 Matthew’s Bible, a bold and often underappreciated compilation by John Rogers, writing under the pseudonym “Thomas Matthew.” Rogers had relied heavily on the unpublished Old Testament translations of William Tyndale, particularly for the historical books.

As a result, the foundation of the Great Bible is unmistakably Tyndale’s. From Genesis through 2 Chronicles, the book of Jonah, and the entire New Testament, the bulk of the text, more than two-thirds, preserves the work of the man once burned as a heretic for his efforts.

To oversee this revision, Myles Coverdale was selected as general editor. The result, printed in 1539 and known as “The Byble in Englyshe of the largest and greatest volume,” was the first English Bible ever authorized for use in churches.

For the first time, the Bible in English was no longer smuggled or hidden, but read openly in churches. Yet it was literally chained, fastened to pulpits to prevent theft and private possession. Only ordained clergy or those licensed by the Church could read it aloud. Yet despite these controls, the impact was massive: the Great Bible brought Scripture in the English tongue to a public audience like never before.

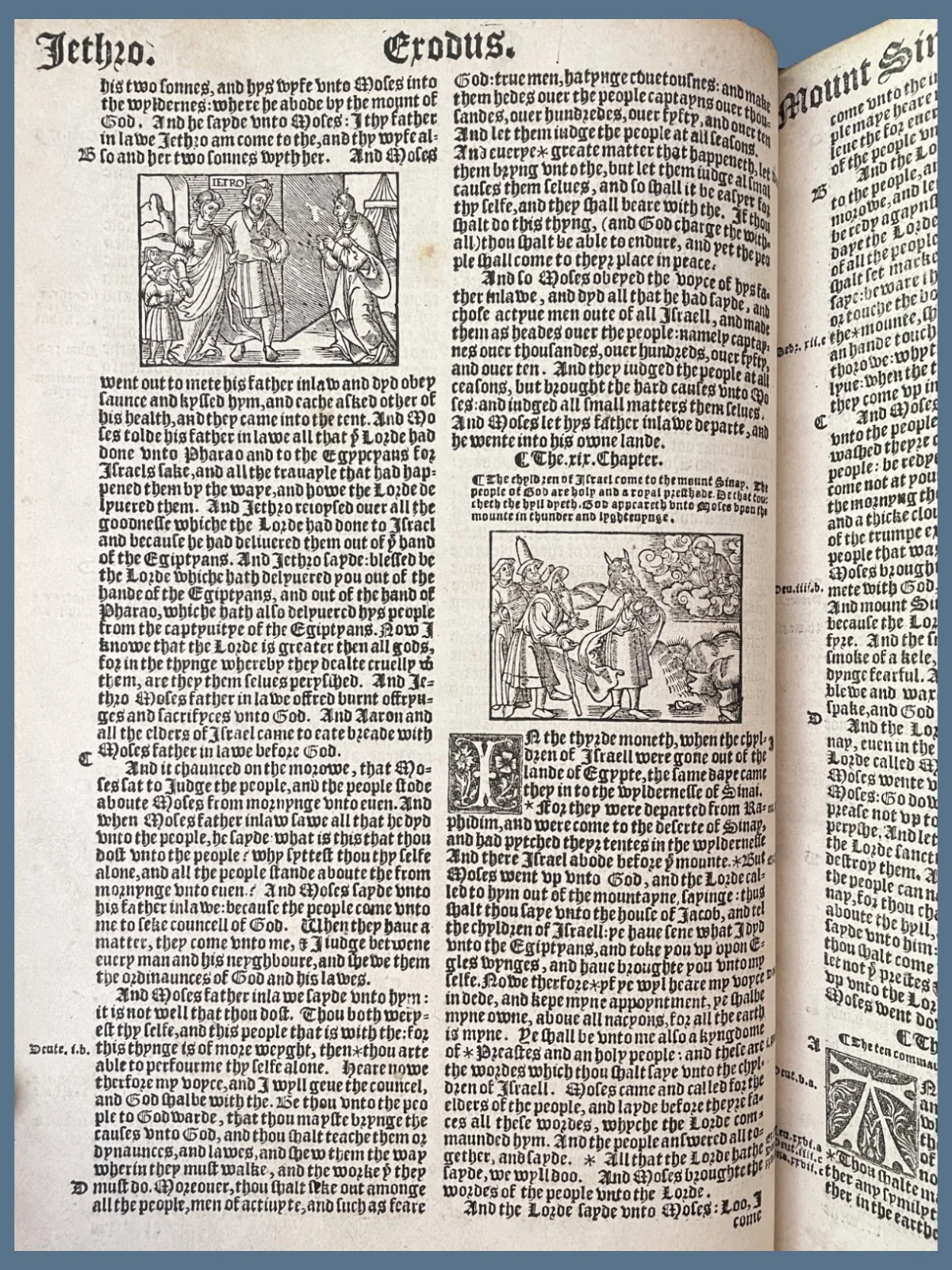

Visually and typographically, the Great Bible is one of the most striking early English Bibles. It contains nearly eighty woodcut illustrations, with text printed in two-column black letter. The beginning of each chapter features historiated or floriated woodcut initials, and occasional metal-cast capitals appear throughout. The general and New Testament title pages feature the striking woodcut described above. Title pages to the second, third, and fourth sections are also printed in red and black, surrounded by rich woodcut borders relevant to each portion of Scripture.

As Bible scholar David Daniell wrote:

“While Coverdale’s revision was generally in a more Latin direction, the parishioner’s encounter with the English Bible was still with the greatness of Tyndale.”

Indeed, the Great Bible not only preserved Tyndale’s voice, but it amplified it. His work would echo well into the seventeenth century, forming the backbone of the 1611 King James Bible, which retains 80–90% of Tyndale’s words.

The Great Bible is the moment when the English Bible moved from persecution to proclamation, carrying forward the labor and legacy of its most important early translator: William Tyndale, rightly remembered as the Father of the English Bible.